There are some special clubs you never want to join, no matter how amazing the members are, no matter what mysteries you will learn about, or how much you’ll grow. There are some ways that one wants to be stretched.

There are elite clubs whose admission fee is far too high, whose membership demands more than an arm and a leg, more than all your stored-up savings, more than all your saved-up strength. There are some which require having your very heart ripped open and then sewn back together to make it bigger.

There are some clubs that will change you more than you ever thought possible—that will transform you into an instrument of healing for others. You will be able to reach people more deeply than ever before, for by your wounds they shall be healed.

These clubs are full of the most courageous, generous people you’ve ever met, who have become more than friends, who are now your sisters, who are family. And yet, like most families, you were born into it by the shedding of blood.

The wisdom gained by suffering is so hard-won.

Oh, would that I were foolish and innocent again! That the world was simple and safe, and heartbreak was but a thing in songs, and not present in the echos of my own heartbeat.

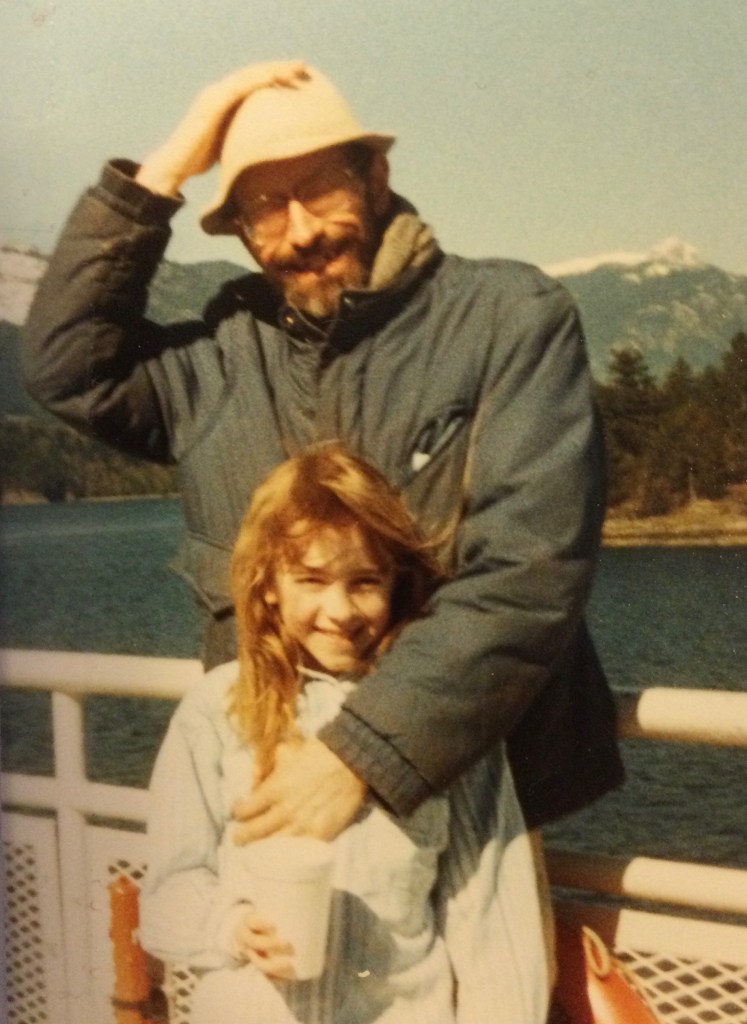

But you cannot return to life before, just as a snake can’t crawl back into its old skin. Your heart has been carved by caverns of sorrow—it will not return to its former shape. This is you now—forever transformed by losing a child. Their very DNA is forever etched into your bloodstream, their silent existence is always in your living breath. You would not have it otherwise—the numbness of forgetting your child would be worse than feeling the pain of a love that never stops reaching for your little lost one.

You see them in the outline of a fallen leaf, in the delicate curve of a snowdrop, in the twinkle of stars between cherry blossoms on a spring night, in the misty face of the harvest moon, distant and ethereal, yet bathing the whole world in its light.

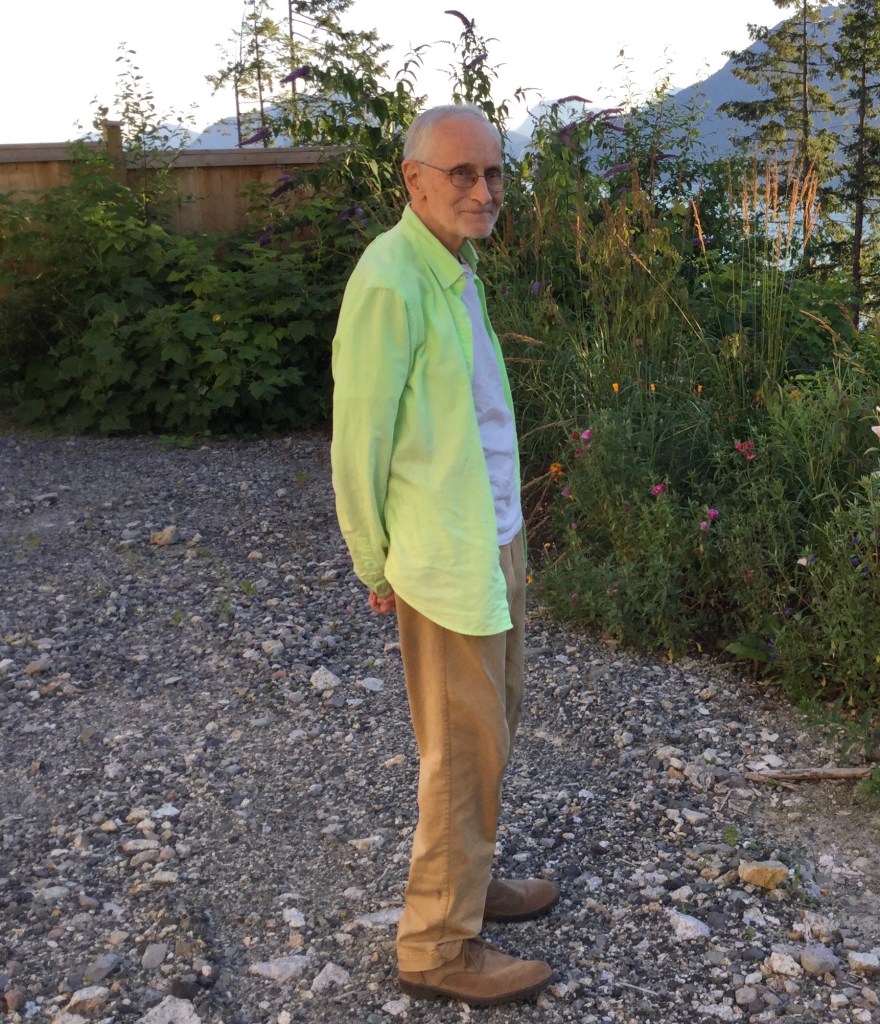

It’s been ten years since my little darling died in labour and I joined the sisterhood of bereaved mothers.

We have no special uniforms or club member pins, come from all social classes and backgrounds and generally walk through the crowds unnoticed. But perhaps you’ll see those extra wrinkles around our eyes because we have laughed and cried so deeply.

Perhaps you’ve felt the sincere warmth of our hugs after you’ve shared your worries with us, and the roaring power of our prayers when you were in labour. Because we know. We know. And we love you enough to wish that you will never join us.

There are enough of us already, and once a member, always a member. No need for yearly dues; your heart, once broken, is payment enough.